A-Yard

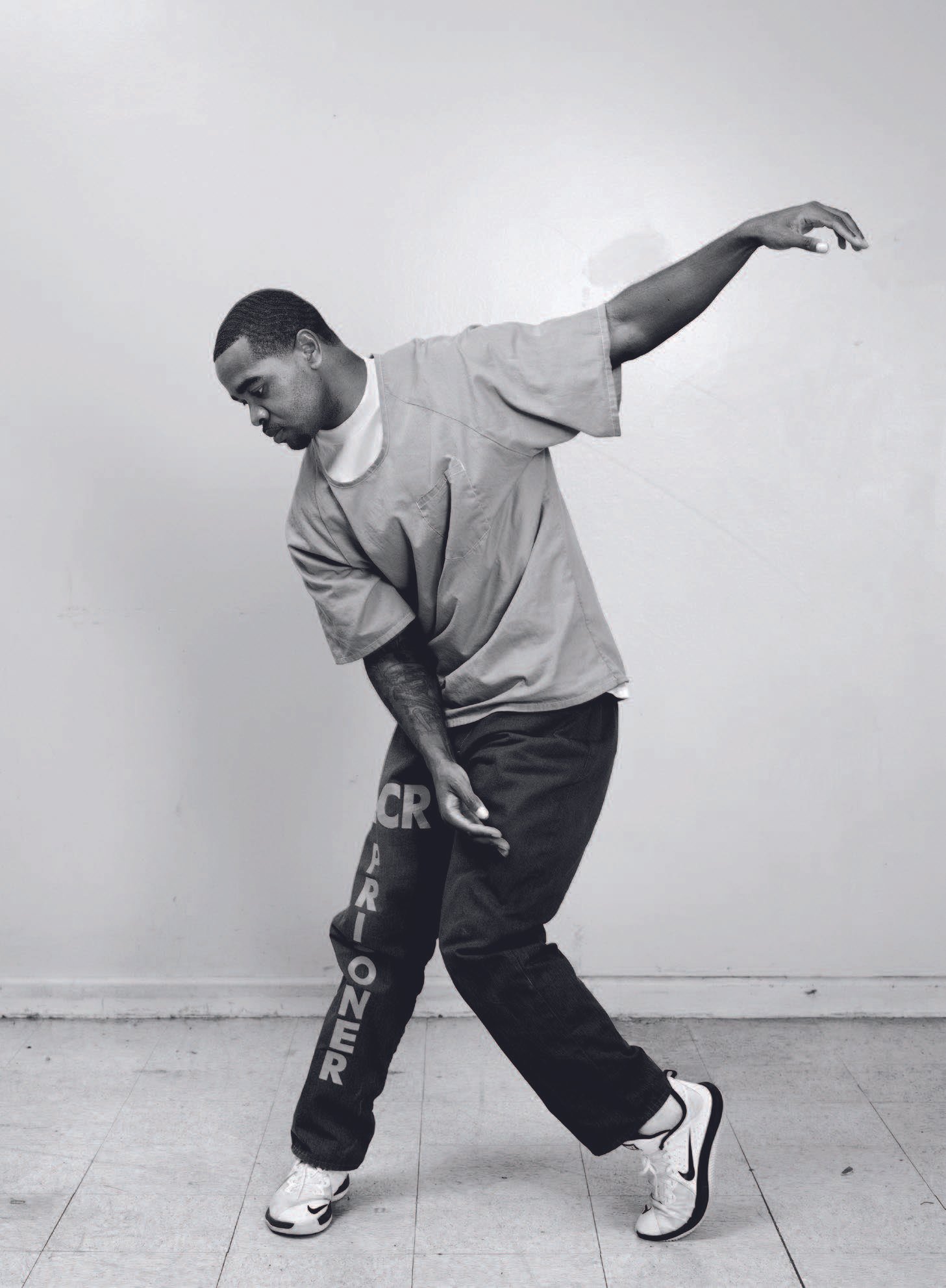

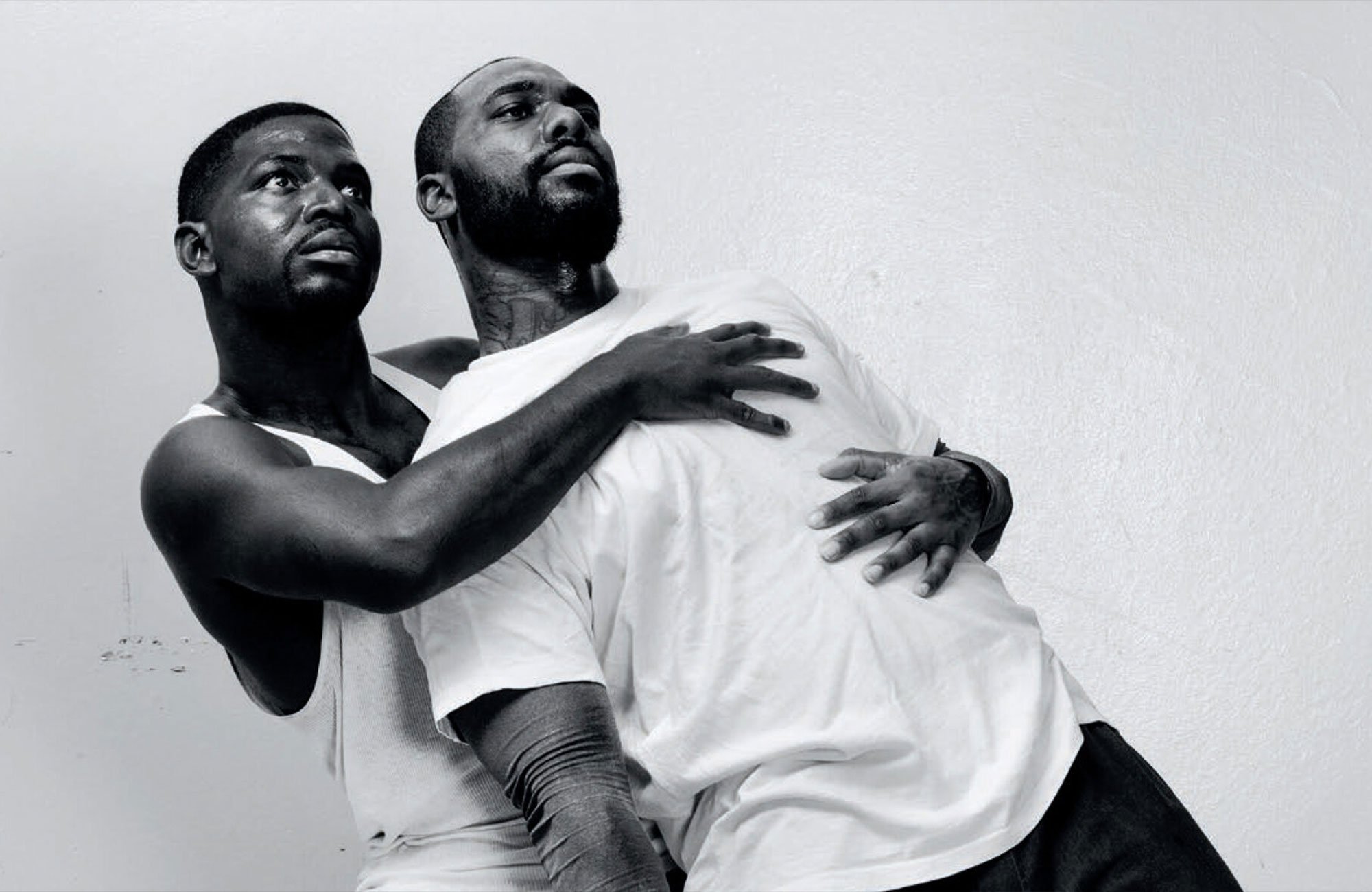

In prisons ruled with toxic masculinity, dancing is an absolute taboo. But at Lancaster, near Los Angeles, French choreographer Dimitri Chamblas has squared up to this notion by creating a dance performance with a group of ten inmates, often former gang members. As an exclusive for Numéro Homme, photographer Pieter Hugo and Delphine Roche, joint editor-in-chief of the magazine, went behind the walls to witness this cultural phenomena.

Quote

How could a choreographer be creative inside a prison with bodies marked by the codes of ultra-virility and conditioned by years of spatial confinement? This is the issue faced by Dimitri Chamblas every week as the Frenchman works on a creation with ten inmates at Lancaster in California, the only state prison in county of Los Angeles.

An hour and a half drive from the megalopolis, the establishment looms large in the midst of a deserted landscape interrupted only by a handful of hotels and fast-food chains. Unlike French prisons which notoriously crowd their detainees into badly-proportioned tower blocks, this institution, opened in 1993, takes full advantage of a very abundant commodity in California (as Noah Baumbach recalls with humour in the recent Netflix film, Marriage Story): space.

Beneath the serene azure of the sky, clean buildings scented with disinfectant alternate over some 106 hectares with vast swathes of open air sections well swept by the violent gusts of wind. In the fenced-off courtyards where prisoners take their constitutionals, dazzling sunlight bounces off the blue uniforms emblazoned with the words CDCR PRISONER.

In spite of the strict structuring of the spaces and the numerous checks carried out on all visitors, the place, appears at first glance, to exude a certain calm, peopled with silhouettes with whom any sort of communication is prohibited, but who seem somehow familiar: the American prison landscape having provided ripe pickings for cinematic and televisual fiction.

“As I began to take classes and learn here, i started to understand what contributed to my beliefs system. That behaviours are learned and also that they can be unlearned.”

Terry Bell

Prisoners are divided into four yards, surrounded by several buildings, each corresponding to the status and level of danger posed by the occupants. Yards B and D house the “general population” while yard A, where the rehabilitation programs take place, is reserved for the prisoners who didn’t commit a disciplinary offence.

Built to hold a little over 2000 detainees, according to a report by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation dated September 2019, the prison is currently home to just over 3000 men. An incredibly high occupancy that reflects America’s passion for locking people up since the 1970s. Initiated in response to an increase rate of crime in the 1960s, this massive and ongoing spate of incarceration means the USA is the country with the highest prison population in the world (in the absence of reliable date from China).

With more than two million people permanently behind bars, it is estimated that 25% of all global detainees are American. In a report entitled Nation Behind Bars: A Human Rights Solution, published in 2014, Human Rights Watch sounded the alarm, revealing that many American laws violated the basic principles of justice by insisting upon punishments that are disproportionately severe in relation to the crime committed. With a 430% increase in detainees between 1979 and 2009, the report noted that incarceration was used indiscriminately in the USA as “the absolute cure for all ills”. It also denounced the way in which this policy weighs heavily on the most fragile and impoverished communities; those that are marginalised by racism and corrupted by violence and drugs.

Like a plague, this infection of incarceration affects mainly young black and Latino men whose profile has become, as much in the eyes of the police as the general public, the identikit picture of a perfect criminal, and the process has created an indelible stigma. For every white man detained in the USA, there are no less than six Afro-Americans currently behind prison walls.

“My brothers were involved in gangs, I was first desensitized to gang culture through my brothers, through peer pressure, the expectations they put on me. I was very sensitive, and they would tease me about being a cry baby.”

Baleegh Brown

A recent article in the New York Times, noted that the number of detainees in California leapt from 20,000 in 1980 to 163,000 in 2006 – and it’s now the state with the second highest prison population in the country, with more than 200,000 prisoners. In the 1990s, a series of draconian laws were passed, explains Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy – faculty director of Cal State LA's prison education BA program and founder of the organisation, Words Uncaged – who offers practical artistic and writing workshops as well as university degrees to the Californian inmates.

“The 1990s in our state were marked by both an epidemic of crack-cocaine use and the apex of gang culture. At the same time there prevailed a myth of the ‘super-predator’, created by the criminologist John Dilulio, according to whom we were going to witness, in the years to come, a real bloodbath committed by very young sociopaths, often Afro-Americans and Latinos. This theory claimed that the young people, often gang members, who committed violent crimes at an early age had a mental nature that was different to the rest of humanity, that they were monsters incapable of any rehabilitation.”

Despite a dramatic drop in youth crime figures, starting in 1995, the laws that authorised a minor to be tried just like an adult were maintained.

“In addition, from 1994 to 2012, the ‘three-strikes law’ made it possible to lock up individuals guilty of petty non-violent crimes for life. A long list of aggravating factors (using a gun, being linked to a gang, etc.) has also been established, meaning an increase in the number of prison years doled out for a single crime. The felony murder law also means that a person accompanying someone who commits murder can be tried for the same crime, even though he didn’t directly participate. Put together, these laws resulted in 16 and 17-year olds being sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Among all the developed and democratic countries, the USA is the only one where a ‘life’ sentence actually means life, implying that these prisoners will die behind bars.”

Dancing in A-Yard

Inspired by Dimitri’s work with inmates and as subject for her new documentary, filmmaker Manuela Dalle followed Chamblas inside prison walls to document this first in its kind interaction.

The documentary film had its first screening to a sold-out audience during the 43rd Montpellier Danse Festival in 2023 and will continue screenings in the USA and Europe in the months to come.

“Beyond the battered lives and a prison system on the brink of collapse, Manuela Dalle's documentary gives us an insight into the ability of every human being to reinvent themselves, given the opportunity.”

Palais des Beaux Arts

Feb 5 - Lille, France

Toronto International Black Film Festival

Feb 17 - Toronto, Canada

The Rough Draft Conference at CalState

Feb 23 - Los Angeles, United States

Montpellier Danse

Mar 5 - Montpellier, France

California Institute of the Arts

Mar 12 - Los Angeles, United States

Cinepolis

Apr 4 - Inglewood, United States

Festival le temps d’aimer la danse →

Sep 11 - Biarritz, France

Chaillot - Théâtre national de la Danse

Sep 21 - Paris, France

As part of Chaillot Experience #1

Wake up Café

Sep 27 - Lyon, France

Maison des Arts du Léman Thonon-Evian-Publier

Oct 4 - Thonon-les-bains, France

2025

The Slit

Feb 1 - Los Angeles, United States

Un toit, une toile

Mar 16 - Paris, France